Basic white Loaf

When learning to bake bread why start with a plain white loaf with a single type of white flour and no whistles and bells?

That’s the point.

There is nowhere to hide with a plain white loaf. You have to get your techniques absolutely right and have a sound understanding of how your ingredients work. It is a great arena for learning how yeast behaves and why. How to knead? Why knead? What is really going on when we prove dough? What happens when a loaf is put in the oven?

If you can get the basics right on a simple white loaf then the bread baking world becomes your oyster.

But by the way, it’s not that simple!

Let’s take a quick look at our ingredients...

Flour

Flour

Flour contains a variety of different substances including protein, sugar, enzymes starch and lipids. Different flours contain these base substances in different quantities depending on what the flour is milled from, for example wheat flour has a lot more protein than rye flour.

You need what is called a ‘strong’ flour or ‘baker’s flour’. It’s strong because it comes from wheat that is hard due to a high protein content compared to starch content. This means that when kneaded the hard proteins form strong bonds which create that lovely chewy crumb texture we get with a decent white bread.

Compare this with a cake crumb where a ‘soft’ or plain flour is used. Here the flour has a much higher starch content which results in the tender crumblier crumb instead of chewy. We hope!

Two of the natural proteins in bread are gliadin and glutenin. Repeated stretching unfolds and then aligns these two proteins and forms ‘gluten’ strands. This makes your dough silky and elastic.

The etymology of the word gluten is from the Latin word for ‘glue’ so it’s no surprise that it’s the gluten which holds the bread together in the structure we associate with white bread by trapping the gas bubbles created by the yeast which in turn forms the crumb.

When dormant the gliadin and glutenin molecules are a tangled mess. When water is added and kneading takes place the molecule structure changes from tangles to straight and aligned. Hey presto, gluten is formed.

Yeast

Yeast

Wow. Yeast is quite a thing and arguably the earliest domesticated organism. The etymology comes through Indo European ‘Yes’ and Old English ‘Gist’ meaning to boil or bubble. And bubble it does.

It’s actually a fungus which comes to life with water and a little warmth and then feeds on the natural sugars in the flour. As it feeds away it burps out carbon dioxide which manifests in little gas bubbles. It’s these bubbles which give air around the glutinous structure of the dough and cause the bread to rise.

There are many types of yeast and it deserves a whole post to itself, but here I’ll concentrate on a single type. Fast acting dried yeast. I’m choosing this type as it’s readily available and the easiest to use. Not that I’m a believer in the easy route but it’s a good way to start out and once mastered you can quickly progress to using fresh yeast.

Water

A lot is written about the temperature the water should be. I have found that a blood temperature works well. Simply dip your finger into the water and if it feels that there is no change it’s the same temperature as you. Or your blood!

Sugar

As we know yeast eats sugar and gives off gas which is what we want to make the dough rise. Be careful though as too much sugar can actually inhibit fermentation. It can also affect the development of the gluten in our dough as it competes with the protein to absorb water. If you have ever made a sweet dough you know that it takes longer to form for this very reason.

It’s also partly the sugar which gives our bread the lovely brown crust we are looking for. Something called the Maillard Effect where sugars turn brown when heat is applied and create depth of flavour. That brown crust in bread gives the whole loaf extra depth and is really important to your final product.

You might wonder why a lot of commercially produced breads contain so much sugar? The answer is that the traditional way of bread baking takes time, care and artisan skills. Something which is incompatible with commercial bakeries because time, care and artisan skills are expensive. So instead of allowing a long proving time they replace the flavour developed during a real proving with artificial flavourings and sugar. Much cheaper and no skill required.

Salt

Salt is a flavour enhancer. This means that used in the right quantities it makes your food taste even more like itself. Tomatoes become more ‘tomatoey’, meat more ‘meaty’. I could go on....

You might think, as I used to, that salt is added only for flavour. But no. It has another important role to play in the proving process. Like sugar, it actually inhibits the yeast activity making the dough rise more slowly and evenly. This creates more flavour.

As it inhibits the yeast eating up all the sugars, salt therefore helps to make sure there are more sugars around to give us that brown crust we are after.

Furthermore, the addition of salt makes the dough stronger as it has a dehydrating effect and tightens the structure. If you make a dough without salt but the same ratio of flour to water you’ll notice the saltless dough is stickier and more likely to rip when kneading.

As a guideline, 1.8% salt to the dry weight of flour is about right.

Butter / Oil

There is much discussed about the benefits of oil or butter added to the dough.

It is widely accepted that the addition of fats will result in a more tender crumb and an extended shelf life. French baguettes have no fat in them and so don’t last as long as those that do. A lot of people argue that bread shouldn’t have a long shelf life anyway and the ability for supermarket breads to last for the length of time they do is positively alarming!

I’m using butter rubbed in at the dry stage here but I sometimes use olive oil worked in at the kneading stage which brings extra flavour.

Now let’s have a look at the crucial stages and processes in chronological order...

The mixing

It sounds obvious but what you are after here is an even distribution of all your ingredients.

To this end, use a ridiculously large bowl. The bigger the better. A simple plastic washing bowl is perfect, if you can get one with a slightly abrasive surface it aids the process.

At this point it is important to let the dough rest in its shaggy mass before you start to knead. This gives the flour time to absorb the water so the dough is less sticky and therefore you are not tempted to add more flour. If you have got your quantities right you shouldn’t need to flour your surface during the kneading process. Do remember however that different flours absorb different amounts of liquids in different atmospheres. You might need to adjust the amount, remember to get an understanding of what the right dough feels like rather than blindly following the recipe.

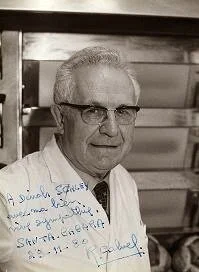

Raymond Calvel

There is much written about the ‘autolyse’ method developed by Raymond Calvel the daddy of French breads which involves letting the dough rest at this stage without the addition of the salt, sugar and yeast. He’s worth looking up.

The Kneading

Kneading develops the gluten which we need for the texture of good bread.

Furthermore, the kneading traps air pockets which hold the carbon dioxide given off by the yeast and provides the structure which allows the bread to rise.

Your dough is kneaded enough when...

It’s a nice smooth consistency. Soft and pliable to the touch.

It holds its shape. The gluten strengthens the dough so it should retain its shape when picked up.

I have found that the best technique is to hold one side of my dough with the heel of my left hand and then stretch the other side away from me with my right hand. Then roll the dough back towards me into a ball again, give it a quarter turn and then repeat.

Under kneaded dough will retain the shaggy mass form and will tear easily. It will not have the strength it needs to hold the gases and structure of the loaf when baking and will therefore spread outwards rather than up and be rather flat. It may even collapse as the gases escape the loaf due to the gluten not holding them in.

Over kneaded dough will go through the correct silky soft elastic stage and then become tough. It will feel tight and you won’t be able to fold it over on itself very easily. This is almost impossible to do if kneading by hand. It’s only with a mechanical mixer that you could work the gluten too much. A good reason to roll up your sleeves and do it the natural way.

Then we leave it to ferment...

The Rising

The dough is covered to avoid moisture loss and left to rise.

All the tiny yeast cells feed on the natural sugars and give off, among other things, gas.

The ideal temperature for this to happen is actually much lower than most people think, about 80 ° F / 27° C. So don’t put in on a radiator or in the airing cupboard. In fact many believe that the lower the temperature; the slower the rise, the tastier the bread. I have often let my dough rise in the fridge overnight with good results.

It’s been shown that yeast produces gas ‘faster’ up to 95° / 35° C but it also tends to produce more unpleasant smelling byproducts as well. So be patient and let nature work its magic in its own time.

When is it ready?

It should be about double in volume.

When poked with a finger it should not spring back. This means that the gluten has been fully developed.

At this point ‘knock back’ the dough by punching all of the air out of it. This redistributes the yeast evenly as well as evening out the temperature.

The dough is then shaped into the form you want to bake it in and, with strong flours, left to rise a second time. This is usually a shorter time.

The Baking

The first thing that happens when you put the dough in the oven is that the yeast has one last hurrah before the heat kills it dead. This is called ‘oven spring’ and manifests itself by a quick rising of the loaf.

Two very important things then happen at the same time.

The gluten coagulates and the starch gelatinizes to create the solid crumb we know in bread.

The crust starts to form on the outside of the loaf and create a crunchy seal.

This is really important when it comes to your oven temperature.

If your oven is too cool then the dough expands before the gluten and starch have set causing the loaf to collapse as there is no solid structure to hold the dough.

If your oven is too hot then the crust will seal the loaf preventing your dough from expanding resulting in a poorer texture.

The crust of the loaf should brown nicely which bring flavour to not only the outer edge but permeates through the whole loaf.

Your bread is cooked when it sounds hollow when tapped and feels ‘light for its size’.

The Cooling

When the loaf comes out of the oven the crust is super hot and dry and the centre is cooler and moist. The bread needs to rest so the temperature evens throughout and the starch has a chance to solidify. Don’t be tempted to cut in too early!

So let’s bake.

Bannetons

I am making round loaves using bannetons but you can use 3 X 500g / 1lb tins.

Ingredients

1000g / 1kg strong Baker’s Flour

14g or 2 sachets of fast acting dried yeast

700ml water at room / blood temperature

18g salt

Utensils

A large mixing bowl

3 Bannetons or small wicker baskets

Electric weighing scales

Baking tray

Cooling rack

Begin by sieving your flour into the bowl. Add in the and dried yeast.

Make a well in the bottom and add in your water. Reserve a little just to make sure you get the right consistency.

You should be able to collect all of the flour and liquid together into a complete shaggy mass with no extra flour left around the bowl.

Turn out onto your work surface and allow to sit for 10 minutes for the moisture to absorb as much as possible before kneading.

Now start to knead. Remember it is the final result of an elastic smooth dough that we are looking for. As you stretch out the dough look for the elongated strands which indicate that the gluten has been aligned.

Really stretch

and roll back

When you are happy, return to a lightly oiled bowl and allow to double in size at room temperature.

When doubled in size knock back and remove from the bowl.

Using your scales divide the dough into equal sizes according to how you are going to do your final prove. I’m using three bannetons so my 1650g of raw dough went into three loaves of 550g.

Shape into a ball by gently flattening and then folding the edges to the middle. Then turn over so the rough folds are at the bottom. ‘Cup’ the ball at the bottom with both hands on either side and rotate the ball thereby aligning the bottom.

I then turned the ball into the floured tea towel in banneton upside down as I will later turn it onto the baking tray back on to the under side.

If you are using loaf tins simply shape the same as the tin and place in the bottom. Remember to oil the tin first!

Leave to prove for a second time until risen again. This will be a shorter time than the first.

Pre heat your oven to 230 ° C conventional and place your baking tray in the oven. If you are using a steam bath technique put you empty tray under to heat up as well.

The dough is ready when you press a finger gently to dent the dough and the dent remains.

Remove the baking tray from the oven and sprinkle with a little flour.

Now turn the dough onto your pre heated and floured tray, spray with water, sprinkle with flour and then very lightly carve two or three lines in the top with a very sharp knife.

Alternatively, brush all over with beaten egg wash for a more golden crust. I personally prefer the more rustic water and flour.

Return to the oven with a big spray of water into the oven or pour cold water onto your heated tray in the bottom of the oven.

Immediately turn your oven down to 200° C

These three loaves took 45 minutes but remember that all oven are different so use your judgment. You want a loaf which is coloured on the crust, feels ‘light for the size’ and sounds hollow when tapped. Those three indicators should do you well.

Sprayed with water and doused with flour pre bake.

Transfer to a cooling rack and leave until cool. Don’t be tempted to slice it open before cool!